Report Writer Taxonomy

Table of contents

Context

When company leadership approached me to enhance our flagship report writing tool’s “look and feel,” I instead argued that improving the information architecture would be a better use of company resources, addressing fundamental accessibility barriers rather than apply cosmetic fixes.

Advocating for systematic information architecture improvements was not just an economical and robust way to reduce mental fatigue for our users working in high-pressure clinical environments, but also to reduce cognitive barriers that affect all users — but disproportionately impact those with varying information processing needs.

Building the case

To effectively advocate for improvements to user-experience and accessibility through information design, I had to craft arguments that would resonate with company figures who had their mind set on short-term visual fixes.

Speaking to leadership, engineering, management, and sales, my presentation highlighted:

- Codifying institutional knowledge to reduce training costs

- Improving user experience without major development work

- Amplifying product strengths by reducing usability barriers

- Standardizing vocabulary to improve marketing and internal communication

- Making our product more accessible to a wider array of potential clients

Behind my decision

I ultimately chose systematic change over visual fixes for several reasons. For one, years of code development had created layers of technical debt that would require significant engineering resources to overhaul. Second, I recognized that things like proper heading hierarchies and label-input pairings would be less consequential if the terminology itself was creating cognitive barriers.

Lastly, the cost-benefit analysis. Rather than building more, I focused on amplifying the inherent institutional knowledge and functionality through clear vocabulary. This path had fewer dependencies, less technical overhead, and offered compounding impact by documenting institutional knowledge that only existed in the minds of our engineers.

Research

To develop and refine the information architecture, I conducted one-on-one interviews with developers, managers, and leadership to map core features, concepts, and functionality. My conversations revealed pain points, inconsistencies, and how language was impacting accessibility.

Building on mental models

When engineers would explained complex features to me, they often arrived at simpler, more intuitive terms with repeated questioning. This revealed how company-specific jargon created unnecessary cognitive barriers when more common mental model could convey equivalent functionality.

Defaulting to power users

The software’s offered extensive customization options for power users in charge of architecting reporting environments for their hospital centers, but this flexibility created cognitive barriers for users who simply needed to run reports efficiently.

The software’s building-block architecture enabled power users to define custom queries, but also exposed these options to the much larger majority of users who would never touch them. The abundance of rarely-used options created decision fatigue and cognitive barriers for registrars whose goal was simply running standard reports efficiently.

A specific example can be seen in a data element selector panel. Users selecting data elements encountered “data element” as an option within the list itself. While relevant to power users, this created a recursive, confusing situation for others.

Development

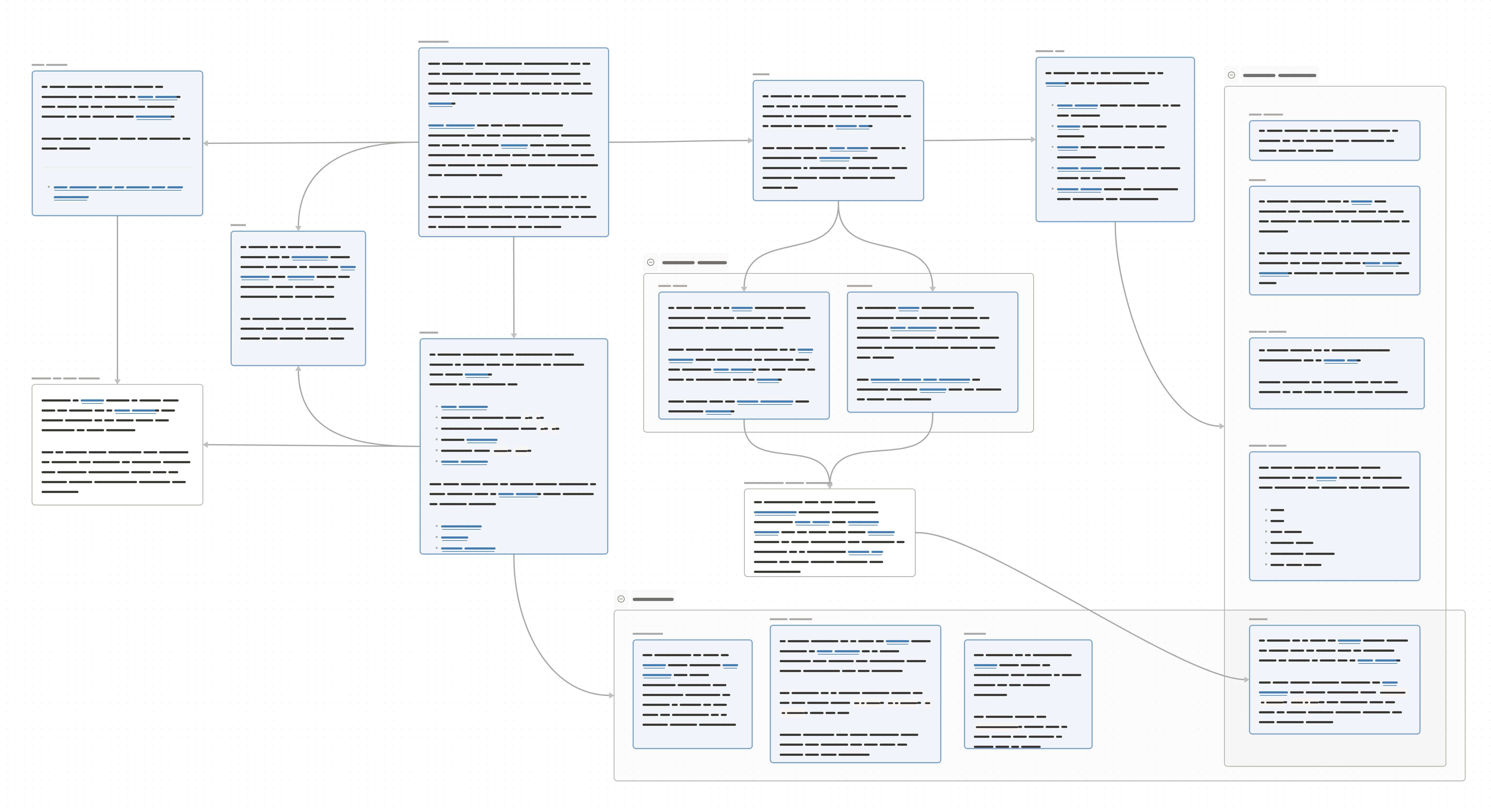

I followed a three-step cycle to build the taxonomy:

- Abstraction — distilling concept purpose, form, and function

- Combination — creating concise definitions with readability scores

- Relation — linking terms to reveal connections and hierarchy

Significance and impact

Complex, niche software terminology creates accessibility barriers that run deeper than HTML structure. Unfamiliar vocabulary conflicts with mental models, adding consequential cognitive load in trauma center contexts.

By establishing a clear, consistent vocabulary for administrative functions and daily operations, this taxonomy serves to reduce cognitive load for task-focused users, preserve the flexibility required by power users. It also follows plain language guidelines in support of cognitive accessibility, laying the foundation for future interface improvements.

Furthermore, by advocating for foundational improvements over visual changes, I demonstrated how systemic thinking enables accessibility from the ground up.

Lessons

Speaking up for shared values

In response to my interviews and design approach, several engineers and managers confided in me that I was addressing concerns they’d felt but hadn’t been able to articulate — things they knew they needed, but didn’t have the experience to put into action. This reinforced for me that accessibility is not something that need be a fight, rather the work of standing up for values people already hold, but can’t act on.

Visibility of progress

Information architecture improvements are less visible than visual changes, making them harder to convey in business contexts. Yet these are exactly the kinds of accessibility improvements necessary to get stakeholders to invest in, rather than quick, surface level fixes. By involving the team in the taxonomy process, speaking to the priorities of each party, I allowed them to internalize the value through participation rather than demonstration.

Strong information architecture creates the foundation for enables subsequent inclusive design — addressing root causes proves more effective than treating surface symptoms in isolation.